- Home

- Inspirations

- Fair Isle in the 1940s and 50s

Influences on Fair Isle knitwear design in the 1940s and 1950s

Joan Fraser

The language of Fair Isle knitting is made up of a great store of patterns and styles gathered over the years from many sources, and it is always evolving. This evolution reflects not only developments in our local culture and markets, but also some major national and world events.

The 1940s and 50s was a time of sweeping change in Shetland. Its geographic location made it a critical base for military defence and surveillance operations during the Second World War, and the resulting influx brought permanent change to the local industry and economy.

There were a number of effects on the Shetland knitwear industry. These included the assimilation of new patterns; accessibility of markets; increased autonomy for knitters; higher prices and the final ascendancy of a cash economy over the last remnants of a barter system. Added to this, the improved infrastructure and communications put in place for the war effort later contributed to the establishment of new factories, extended outworking systems, mechanisation and marketing.

The Norwegians arrive

The Germans invaded Norway in 1940 and occupied the country for the course of the war. During that time around five thousand Norwegians escaped and the great majority came to Shetland. Some were brought by means of the Shetland Bus, a clandestine boat service between Shetland and Norway. Others came independently and there were some hazardous trips in open boats. Many of the refugees remained in Shetland throughout the war years. As the war progressed local accommodation became scarce, but Shetland was still a staging post for refugees who moved on to accommodation on mainland UK.

Added to this influx, six hundred Norwegian servicemen were based in Shetland. Their work included the Shetland Bus operation which besides transporting refugees had various military objectives.

The Norwegians were treated with great hospitality, and the prolonged interaction had a considerable impact on the local culture. Over the years friendships were forged and marriages made, as well as business and community links. Just as significant, where the groups shared daily life and work, there would have been a routine and natural exchange of many aspects of domestic culture.

The Norwegian large star pattern

A knitwear-related result was the local rise in popularity of the Norwegian large star pattern. Knitters would have copied this from the clothing of the Norwegians.

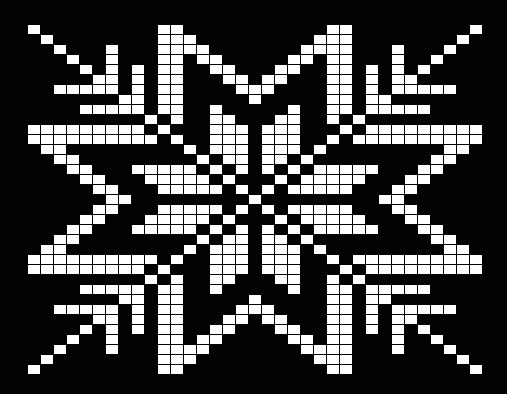

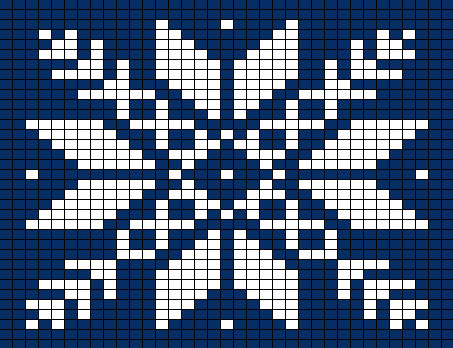

A Norwegian large star pattern

However the Norwegian patterns were not adopted wholesale, but were integrated according to the 'rules' of Shetland knitting. As Sheila McGregor points out the Shetland knitters liked to 'close off' patterns, so that lines linked up in 'a satisfying space enclosing way'. So for example the star patterns were integrated into the Shetlanders' horizontal banding scheme and small motifs were sometimes added at the corners. McGregor also says that the Norwegian open diagonals were mostly edited out by Shetland knitters in favour of more concrete designs.

One of the most elaborate ways in which the Shetlanders used the star pattern was in vertical panels. These were more complex to design and knit than the horizontally banded patterns, and many were highly intricate. The panel designs were particularly popular in the islands of Whalsay, Skerries, Yell, Unst and Fetlar. Mary Smith's book The Shetland Knitter's Handbook features some beautiful examples from some of these islands.

Detail from a vertically panelled jumper with the large star pattern in the main panels, smaller patterns in neighbouring panels and patterned borders in between This example also shows the Shetland application of different coloured bands. This is a detail from a man's allover patterned jumper currently on display at the Shetland Museum.

Another change Shetlanders made in their adoption of the Norwegian patterns was in the use of colour. Whereas the Norwegian stars were traditionally knitted in one colour against a contrasting background, the Shetland knitters introduced colour bands to the pattern and often used bright colours in the middle.

Detail of a large star pattern made popular during and after WW2. In Norway such patterns were knitted in two colours. You can see here the application of the Shetland use of colour. This is a detail from a man's allover patterned jumper currently on display at the Shetland Museum.

It should be noted that the large star did not arrive exclusively from Norway, nor only at the time of WW2. However the great influx of Norwegians at that time and the exposure to their culture would have been the cause of its sudden popularity.

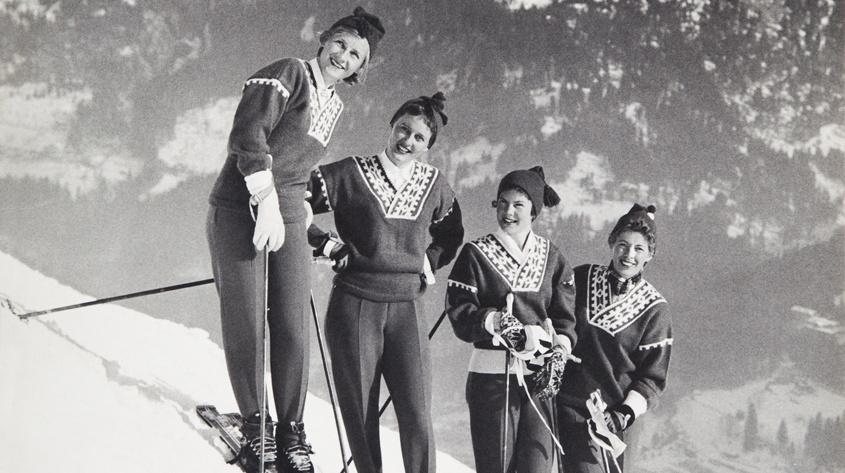

Just as Shetland retained a general appreciation of things Norwegian, its knitters and designers favoured Norwegian-style patterns throughout the 1950s and well into the 60s. This fashion was not only local. Internationally, Norwegian knitwear had become highly popular when the company Dale of Norway designed and produced the outfits of the 1956 Norwegian Olympic ski team.

The 1956 Norwegian Olympic Ski Team. Image Courtesy of Dale of Norway.

Gloves designed by Theodora Coutts who was a leading Shetland designer and an enterprising businesswoman. Many of her designs had a strong Nordic flavour.

The remarkable assimilation of the star motif into Fair Isle knitting shows how fluid the visual language of pattern can be. Nowadays, many Fair Isle garments in the shops feature these star patterns. They actually predominate in an online image search for Fair Isle pattern. It would be difficult to imagine Fair Isle knitwear without these patterns now.

A better deal for knitters

During the war large numbers of British servicemen were stationed in Shetland, because of its strategic location in the middle of the North Sea. At the peak of the war effort there were around twenty thousand servicemen, outnumbering the local population. At the same time, many UK factories had stopped producing woollens for civilians and were concentrating on military contracts. This resulted in a ready market for hand-knitted goods as servicemen bought garments for themselves and also gifts to send home to their families.

Another result of lost production from factories and other suppliers was that large British retailers began sourcing knitwear directly. Some, such as Marks & Spencers, advertised for local knitters in the Shetland Times.

These developments did not only mean a steady demand and higher prices for knitwear. The real game-changing effect was that knitters were freed from their dependency on local merchants. This dependency was a hangover from the truck system by which workers were paid in commodities often controlled by a single laird or merchant. The system had been repeatedly legislated against, and had also been eroded by a gradual improvement of living conditions during the early 20th century. However it lingered on as part of life particularly in some rural areas, for various reasons. These reasons included lack of a reliable cash economy to replace it; the inertia of existing practice; and limited access to alternative markets.

I know a sister and brother who remember knitting spencers as children before the war, when they would have been about eight or ten years old. Their mother of course also knitted. The family took their products to the local shop and exchanged them for groceries. For this family and others such a barter system had long been accepted as one of the few reliable means of putting bread on the table. The sister and brother have told me they saw it as a not altogether bad system in an economy where there was little ready cash. There had, at any rate, been little option.

Even knitters who were selling to hosiery shops for cash had been receiving a pittance. But from around 1940 and throughout the war knitters were able to sell direct to customers, and payment was in cash. Knitters had a choice as to where to sell, and could bargain for a better deal. Whilst knitting income had previously brought food to the table, it could now bring money into the household. The general high employment of the war years was also a major factor in reducing families' dependence on barter.

And of course, there was a certain circularity: within an expanding cash economy, money was becoming even more essential.

Mechanisation and the Fair Isle yoke

After the war, there was suddenly less access to direct sales. However improved infrastructure and communications which had been put in place for the war effort were of benefit to local industry, and there were much improved trade links with the UK mainland. New knitting factories were established. These mainly dealt in plain knitwear. One patterned exception was the Fair Isle yoke. The plain bodies of jumpers and cardigans were machine-knitted in the factory, and then the garments were sent out to outworkers all over Shetland for the handknitting of the Fair Isle yokes.

These yokes usually featured a Norwegian star and tree pattern. They were exported mainly to France where they were popular for a while. The jumpers, with their high-ish crew necks and patterned yoke were not particularly flattering on many figures. The yoked lumber cardigans did have more style, mainly because the shape is enhanced by being left open, and it is these which have recently come back into fashion in Shetland.

Many people who were knitting in Shetland in the 1950s have little affection nowadays for yoked garments, associating them with the external pressure that home-based piece work brought. Not only this, but the factories supplied and stipulated the wool colours to be used for the order so there was no real creative enjoyment for the knitter. However the style worked well for a while: being both mechanically-made and uniquely home-crafted, it was a good practical compromise for the factories and the market.

I have never knitted a yoke, and didn't think I liked them. All the same, I now find there is something quite beautiful about this plain garment with its deep collar of pattern.

This yoked cardigan, with its picot-like edge to the yoke and the subtly shaded greens in the pattern, is really quite lovely.

Shaded patterns

In the 1950s shaded patterns became popular. This was probably mainly because of a great increase in the variety of wool colours, and there being more money available to buy them and build up a small stock.

However a further reason for the popularity of shaded patterns may have been the knitters' increased skill and confidence with colour. As Alice Starmore suggests, the wartime knitters who dealt directly with their customers had a new artistic freedom which would in turn have helped them develop a mastery of colour combination.

And so shaded patterns, too, became part of the language of Fair Isle. Later knitters growing up took these patterns for granted, and applied them with natural ease.

That's the thing with language. You understand it because you are in it. It shapes the way you see things. And it keeps changing, we all keep changing it.

JF

With my grateful thanks to Dr Carol Christiansen, Curator at the Shetland Museum and Archives, for her time and expertise.

“7 young men arrived in Baltasound after a 2 day sail from somewhere north of Bergen with no compass, no log, but a good watch and just enough fuel for a straight run”

from an account of Norwegian refugees arriving in Shetland, in Elizabeth Balneaves' book The Windswept Isles.

Further information:

Abrams, L. Myth and Materiality in a Woman's World: Shetland, 1800–2000. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2005

Balneaves, Elizabeth. The Windswept Isles: Shetland & its People. Butler & Tanner Ltd. 1977

Fryer, L.G., Knitting by the Fireside and on the Hillside. Lerwick: The Shetland Times Ltd. 1995

McGregor, S. The Complete Book of Traditional Fair Isle Knitting. London. B T Batsford. 1981

Smith M & Bunyan, C. A Shetland Knitters Notebook. Lerwick: The Shetland Times Ltd. 1991

Starmore, A. Book of Fair Isle Knitting. The Taunton Press. Newtown, Connecticut, 1988.

The Shetland Bus: website commemorating the Shetland Bus operation. http://shetlandbus.com/