- Home

- Inspirations

- Fair Isle in the 1920s and 30s

Influences on Fair Isle knitwear design in the 1920s and 1930s

Joan Fraser

Probably the most intensive period of innovation in Fair Isle knitwear design took place in the 1920s and 1930s. Exhibits and illustrations from this time show a spate of experimentation with motifs and patterns, garment types and shapes, colours and alternative fibres.

I recently visited the Shetland Museum Store to meet with Curator Dr Carol Christiansen, and to examine some examples of knitwear from that period.

The changing role of women

Dr Christiansen told me that one of the driving forces in knitwear innovation was the changing role of women during and after the war. Many young women had found war-time work in relatively well-paid ancillary roles. Meanwhile Shetland lost a higher proportion of men in the war than did any other part of Britain. The resulting post-war surplus of women over men meant that women took on more of the traditionally male jobs.

A number of these jobs were shop-based, office-based and administrative, and more likely to be paid in cash than earlier female occupations. Knitting, for a few, became a source of secondary income rather than a subsistence activity.

The loss of men had also put an end to the already tenuous existence of some of the less viable crofts, especially in areas with poor access. A great number of crofts had in any case been broken down, generation on generation, into parcels of land too meagre to sustain their inhabitants. Knitting had long been the mainstay of crofting households and many of the women, on leaving the rural areas for the main town of Lerwick, took in work as knitters or dressers of hosiery.

The decline of the herring industry – in a large part due to post-war upheaval in Germany and the effects of the revolution in Russia (global markets ruling, then as now) – left yet more Shetland families in desperate circumstances. Between 1921 and 1931, 9.8 per cent of the population emigrated. It is not surprising that these years of drastic social and economic change should impact not only on the working lives of those left behind, but on every aspect of our culture.

The masculinisation of women’s fashion

Nationally and internationally, women’s fashion had taken on a more boyish look, reflecting the post-war roles of women and also new attitudes brought about by the women’s movement. (Even in Lerwick there was a suffragette association from 1909). Corsets, which had been all about exaggerating womanly proportions, had fallen out of favour. 1920s dresses with their dropped waists and looser style were designed for a flatter-chested, androgynous look. In France, Coco Chanel wore trousers, her hair cut in a short bob. When Fair Isle V-neck jumpers became fashionable for men, they became so for women too.

|

| The Fair-Isle Jumper by Stanley Cursiter, painted in 1923. Oil on canvas, 102.2 x 86.6 cm Collection: City of Edinburgh Council Photo credit: City of Edinburgh Council, City Art Centre |

For Shetland's country girls moving even a small distance from their families and into town, there would have been some small sense of cultural and sartorial freedom. While their mothers and grandmothers continued to wear the shawls and long dark skirts of a previous age, these young women became aware of newer modes of dress including the vogue for Fair Isle. Through the 20s they began to see Fair Isle worn by the wealthier classes around town, and to think of it as something they too might wear. Perhaps this helped to inspire the knitwear some of them produced for cash in their spare time, even if they could not afford the time or money to make or buy Fair Isle for themselves.

Economic influences on the knitwear industry

The fashion for Fair Isle grew in parallel with the post-war developments in the labour market, and in parallel too with economic influences on the knitwear industry.

During the war, Shetland knitters had benefited from selling directly to servicemen stationed in the islands. After the war the most skilled knitters were reluctant to return to the local merchants, and continued to sell direct to the customer if they could. Others could demand a higher price from the merchants.

The war had also caused a sharp rise in wool prices. This made it difficult for those knitters who did not have their own source of wool, and must have been a common problem as more people gave up their crofts and moved to town.

There were other pressures on the industry. Machine-made underwear and plain garments, which had been unavailable during the war, now came back on the market. These garments were uniformly sized and less expensive than their hand-knitted counterparts, and Shetland’s knitters of plain goods were priced out.

Lace knitting, which had previously commanded a high price, had fallen out of favour for its fragility and impracticality.

Entrepreneurial innovations

Before the 1920s Shetland knitwear sales had been very gender-specific: there were ‘frokes’ for men and lace shawls for women. Then in 1920 advertisements appeared in the Shetland Times from London-based traders, requesting handknitters to knit jumpers. The jumper was a new type of garment that could be worn by either gender.

Around this time James A Smith, a major Shetland hosiery dealer, gifted a Fair Isle jumper to the then Prince of Wales who was portayed wearing it in 1921. The Prince wore clothes well and was a real fashion icon of the time: Fair Isle knitwear could not have had a better brand ambassador. Alice Starmore asserts that this was the single most important event in the commercialisation of Fair Isle knitting.

Another presentation of Fair Isle to royalty was made in 1922, when two Fair Isle jumpers were included in Shetland's wedding gift for the Princess Mary.

Fair Isle had been embraced as the ideal gender-neutral fabric, and Shetland of course was the place to source it. Unlike plain knitwear, Fair Isle could not yet be produced by machine.

|

| The famous image of the Prince of Wales, later Edward VIII, wearing a Fair Isle sweater in 1921. |

|

|

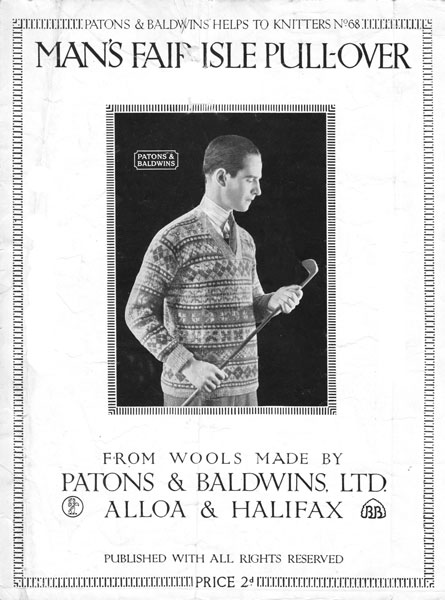

1920s knitting pattern |

In Shetland, superior knitters of both lace and plain goods turned to knitting Fair Isle. At first most of these garments were not produced to be worn by the knitter or the knitter's family: they were made, often to order, for a wealthy fashion market far beyond Shetland.

New designs and their origins

As Fair Isle became a focus of fashion a new energy entered the designs, and there was great interest and confidence in devising new patterns and trying out alternative colours and materials.

In Shetland there were a few notable designers. One was Ethel Brown, who owned a well-to-do hairdressing salon and was married to an artist. She was comfortably off and holidayed in London. She studied the old Shetland patterns and kept abreast of developments in the world of fashion. She was a gifted designer and also rather glamorous, and in wearing her own work encouraged the popularity of Fair Isle in Lerwick society and beyond. A clever and innovative knitter and designer was Jeannie Jarmson. She was boldly experimental (see the yellow tartan slipover below) and worked in both wool and rayon.

Often, however, the design of a piece was not in the hands of the knitter. The jumpers presented to Princess Mary as mentioned above were designed by David Sutherland, a Lerwick watchmaker renowned for his artistic talent. Many garments were commissioned from outwith Shetland, with their colours already specified by the customer (who might have been either a merchant or the ultimate wearer of the garment). Perhaps the customer also sent swatches, from garments with patterns or colours currently popular, to be copied. This material and ideas coming into the islands would have introduced fashionable colours and new patterns into the lexicon of the knitter.

One of the most exciting aspects of this fertile period in Fair Isle design is that it was not relying mainly on old patterns: it was also buzzing with new ideas from a great wealth of sources. New patterns came not only as a result of customer requests but were gathered by knitters from various influences. This was partly due to necessity: patterns had rarely ever been written down, and few households possessed Fair Isle garments from which to copy. Therefore knitters of the time took inspiration not only from Fair Isle patterns but also from other pattern types found in woven textiles and printed materials. There was also experimentation with new synthetic fibres such as rayon.

|

|

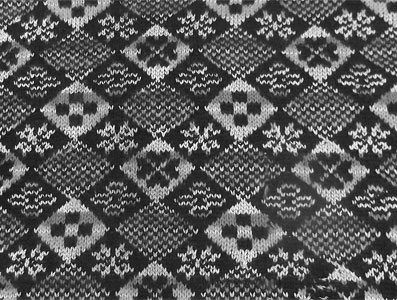

| The slipover belonged to Captain William Jamieson, born in Vidlin in 1908. The garment is thought to have been knitted by his neighbour Anne Jamieson in the late 1930s. It has a beautifully bold and simple diamond repeat which clearly has some influence besides traditional Fair Isle pattern. It is knitted mostly in rayon, but with occasional rows of wool which help it to hold its shape. The wool rows also give a lovely variation in texture. | |

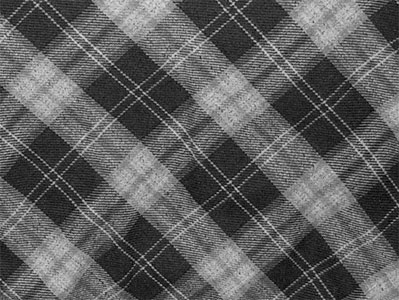

Some patterns were intentionally designed to identify with well-known woven materials. The distinctive slipover below was knitted by Jean MacPherson (nee Jarmson) around 1933/34. The pattern is the McLeod tartan. In the original woven tartan, mid tones or blended colours are achieved by the crossing of differently coloured warp and weft threads. In this knitted version the effect comes from the mixing of the two pattern colours in one-and-one birdseye. This garment has been knitted in a very tight tension, probably to emulate the close texture of woven fabric.

Whilst a garment like this was obviously not intended to be in the Fair Isle tradition, it is easy to imagine that it contributed to the spirit of innovation surrounding Fair Isle knitwear at the time.

Slipover knitted by Jean MacPherson (nee Jarmson) around 1933/34. The pattern is the McLeod tartan.

The diced pattern

The diced pattern became very popular in Fair Isle garments around this time. The pattern intrigues me because it is suggestive of woven plaid cut on the bias. As with the 'tartan' above, the one-and-one birdseye is used to achieve blended colours and mid tones. The diced patterns are said to have come from Scottish kilt hose. Perhaps these in turn had been inspired by woven plaid.

|

|

|

| Two examples of woven plaid fabric on the bias, and a detail from a knitted diced pattern jumper. (Examples shown here in grey to illustrate similarities in tonal effect from the different techniques.) | ||

The diced pattern gives a freedom from Fair Isle's horizontally banded appearance. The familiar Fair isle X and O motifs can still be used, but within the unifying structure of an allover diamond repeat. The pattern became popular for men’s slipovers, sleeveless V-necked garments to be worn with a tie under a jacket. Possibly the pattern had a more cosmopolitan appearance than traditional Fair Isle.

|

| Shetland wool and rayon jumper, made by Ottie Aitken, Eastshore, Virkie, for a boyfriend, Andrew Cheyne, Longfield. Each row of motifs within the diamonds is different, but the overall structure helps to prevent the pattern looking too 'busy'. |

There were many experimentations in Fair Isle design over those two decades. Some of the new patterns and ideas have been absorbed into the medium and are part of what we call Fair Isle today. But perhaps more importantly, the innovative spirit was carried forward and has kept Fair Isle alive and always changing, ever able to absorb new influences, to have other meanings for other times. I wonder, what will Fair Isle look like in another hundred years?

It is both humbling and inspirational to reflect on the vitality at work in that early designer arena: the creative entrepreneurship of the fashion-watching traders, the intuitive skill of the most gifted of knitters, the transactions and collaborations between the two groups; the crossover of visual inspiration; the commerce, innovation and cultural exchange and its influence down through all these years.

It has been fascinating to consider that post-war upheaval, with all its social and economic consequences, should have brought such attention, and such a transformation, to this ancient and idiosyncratic textile and its production in this far-flung location.

And correspondingly it is possible to see Fair Isle pattern as a visual, tactile language, which like any of our languages carries within its body innumerable abstract hints as to the history of our conflicts and discoveries, journeyings and trade.

Men’s sartorial liberation

As a final note, I have been intrigued to find that the masculinisation of women’s fashion was clearly not a one way street. The popularity of the Fair Isle jumper signified a temporary return to more flamboyant dressing in men.

One would think that Fair Isle with its multi-coloured patterns and often rather floral motifs might have been too decorative to be considered truly masculine in the 20th century. However as Christine Arnold says in her article on gender dynamics in Shetland knitwear: “Fair Isle knitwear did and does allow men a certain amount of the sartorial display enjoyed by Scottish men. ...The Scottish male national costume champions male decorative display. This is considered masculine and encouraged by all the generations.“

Indeed, many societies still encourage colourful male dress and do not look upon it as dandified. And as Dr Christensen points out, today’s necktie is in the same tradition as the showier clothing worn by the 18th and 19thth century gentleman. His ornate silk waistcoat with floral motifs and fancy buttons, just visible beneath his coat, was in its own turn an echo of the more conspicuous dress of an earlier age.

It could be said, then, that just as the Fair Isle jumper allowed women freedom from the restrictions of ‘female’ clothing, it liberated men to be a little more in touch with their peacock side.

JF

With my grateful thanks to Dr Carol Christiansen, Curator at the Shetland Museum and Archives, for her time and expertise.

The museum store is available for anyone to visit by appointment. http://www.shetland-museum.org.uk/index.html

References:

Abrams, L. Myth and Materiality in a Woman's World: Shetland, 1800–2000

Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2005.

Arnold, C. An Assessment of the Gender Dynamic in Fair Isle (Shetland) Knitwear, in Textile History; 41, 1; 86-98. 2010

Fryer, L. G. Knitting by the fireside and on the hillside": A history of the Shetland hand knitting industry c.1600-1950. Lerwick: Shetland Times. 1995.

Hughson, H. Ethel Brown: A Shetland Hairdresser and Designer Knitter, in The New Shetlander, 2002, No. 221, pp. 37-40

Starmore, A. Book of Fair Isle Knitting. The Taunton Press. Newtown, Connecticut, 1988.